Pancreatic Surgery

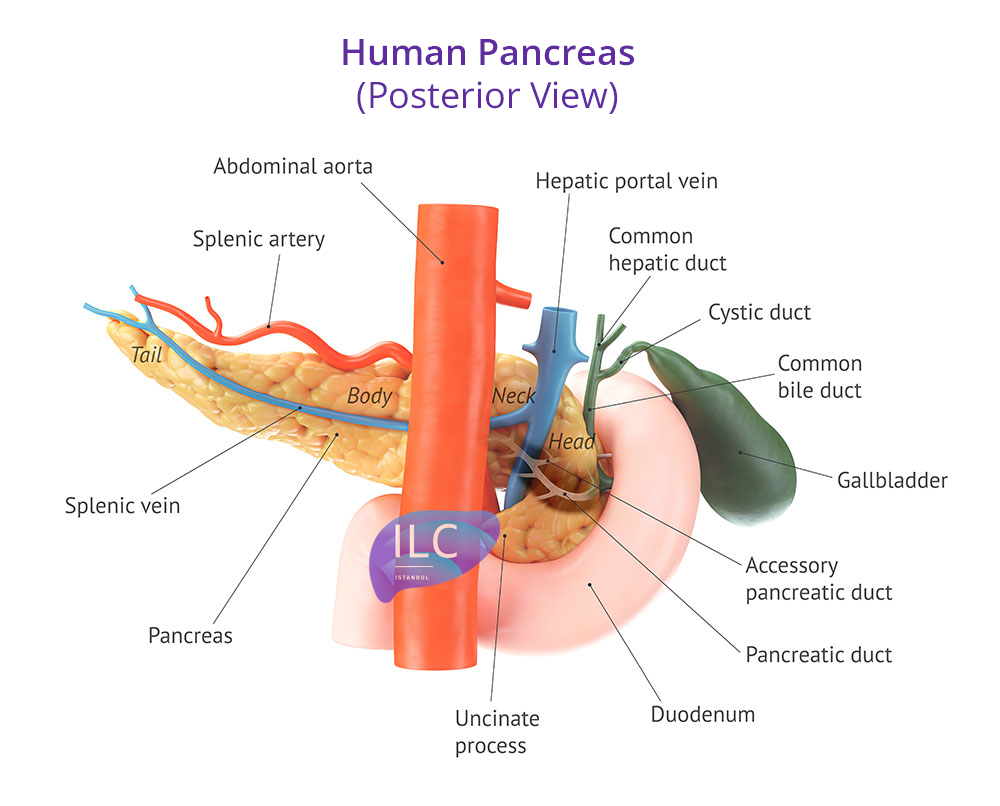

Pancreatic surgeries hold a unique position compared to other general surgical procedures in the eyes of both surgeons and patients, for several reasons. The pancreas’ complex anatomy, its proximity to multiple vital organs, its close relationship with major blood vessels, the need for vascular interventions during pancreatic surgery, the relatively high rate of postoperative complications, and the limited exposure to such cases during standard surgical training all contribute to the distinct nature of pancreatic surgery.

Pancreatic surgery is one of the specialized areas within general surgery. In our country, general surgeons are qualified to perform all types of pancreatic operations. However, due to the broad scope of general surgery, subspecialties have emerged. Liver, biliary tract, and pancreatic surgery is one such field. Surgeons who have received specialized training in this area, either domestically or abroad, often narrow their focus to gain deep expertise in pancreatic procedures.

Surgeons who dedicate their practice exclusively to this field—just as in many countries around the world—help ensure that pancreatic surgeries are performed with minimal risk in our country as well. Numerous studies have shown significant differences in outcomes between experienced surgical centers and those with less experience in pancreatic surgery.

Pancreatic operations vary widely in type and complexity. Not all surgical procedures involve the same level of difficulty, but some of the most complex and demanding procedures in general surgery are related to the pancreas.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Also known as the Whipple procedure, this operation has shed its former reputation due to the successful outcomes achieved by experienced centers today. Introduced into clinical practice in the 1930s by American surgeon Allen Whipple, this procedure continues to be widely used for the surgical treatment of pancreatic cancers. While the postoperative mortality rate was around 30% in the early years, it has now decreased to about 2% in specialized centers. However, in centers without dedicated expertise in this area, the rate remains around 15%. For comparison, the postoperative mortality rate for gallbladder or hernia surgery is about 0.01%.

The Whipple procedure is most commonly performed for pancreatic cancer, but it is also used for several benign conditions. Chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cysts, and particularly intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) are among the frequent indications for this surgery.

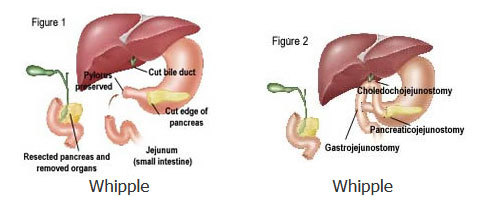

In the classic Whipple procedure, part of the stomach, the duodenum (first part of the small intestine), a section of the small bowel, the head of the pancreas, part of the bile duct, and the gallbladder are removed. The remaining portions of the stomach, pancreas, and bile duct are then connected to the small intestine. In the pylorus-preserving Whipple, the stomach is left intact, and a portion of the duodenum is preserved. There is no significant difference in long-term outcomes between the two techniques.

When performed for pancreatic cancer, the Whipple procedure may occasionally require intervention on nearby vessels (such as the superior mesenteric vein or portal vein) depending on the tumor’s location and extent. Although vascular involvement is not a contraindication for surgery, it increases the complexity of the procedure and therefore requires the presence of highly experienced surgeons.

The average hospital stay is 7–10 days. The duration of intensive care varies depending on the center’s protocols and postoperative complications. As with any surgical procedure, issues such as wound infections or pulmonary complications can occur. The two main complications specific to the Whipple procedure are delayed gastric emptying and pancreatic anastomotic leakage.

Delayed gastric emptying presents as vomiting or the inability to remove a nasogastric tube — a tube inserted through the nose that extends into the stomach. This condition, which can be described as the stomach’s inability to empty its contents for various reasons, is not life-threatening but can prolong hospitalization. In general, treatment involves keeping the nasogastric tube in place for a longer period.

Pancreatic anastomotic leakage refers to the leakage of pancreatic fluids into the abdominal cavity through the new connection created between the pancreas and the small intestine. It occurs in about 15–20% of patients after a Whipple procedure. Most cases are managed by keeping the surgical drain in place for an extended period; however, in some patients, this complication can become life-threatening.

Distal Pancreatectomy

Distal pancreatectomy involves the removal of the body and tail of the pancreas. In practice, any surgical procedure in which the pancreatic tissue to the left of the pancreatic head is removed—regardless of size—is referred to by this name. It is used in both cancer surgery and for benign tumors. When performed for pancreatic cancer (adenocarcinoma), the spleen is also removed along with the pancreas. This is because the lymphatic drainage of the pancreatic body and tail is located in the area between the pancreas and the spleen. Since the removal of the lymph nodes draining the tumor is a fundamental principle of cancer surgery, the spleen is also removed. In distal pancreatectomies performed for other reasons, efforts are made to preserve the spleen; however, since the splenic artery and vein are closely associated with the pancreas, preserving the spleen is not always possible.

The most common and procedure-specific complication of distal pancreatectomy is a pancreatic fistula. When part of the pancreas is removed, the ducts that carry pancreatic fluid to the intestine are also cut. The remaining end of the pancreas is closed either with sutures or with an automatic stapling device. However, pancreatic fluid containing digestive enzymes may leak between the sutures and drain through the surgical drain. If this leakage continues for several days or longer, it is referred to as a pancreatic fistula. When the fluid is drained externally in a controlled manner, it does not cause harm to the patient, though the drain may need to remain in place for an extended period.

The mortality rate after distal pancreatectomy is very low. In recent years, this procedure has increasingly been performed laparoscopically (minimally invasive).

Chronic Pancreatitis Surgery

When surgery is required for chronic pancreatitis, several options are available. If an inflammatory mass develops in the head of the pancreas or if there is an obstruction of the bile ducts and/or duodenum, the preferred procedure for many years has been the Whipple operation. The Whipple procedure is still occasionally used for this purpose. However, due to the risks associated with Whipple surgery, it may be too aggressive for some patients with chronic pancreatitis, a benign condition. Therefore, alternative surgical methods have been developed.

In chronic pancreatitis, the pancreatic duct enlarges due to inflammatory strictures and the presence of stones within the duct. In patients without an inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head but with a dilated duct, a new channel is created between the pancreatic duct and the small intestine. This procedure is called the modified Puestow operation. It has a very low complication rate and relieves pain in about 80% of patients.

For patients with an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas, another option is partial resection of the pancreatic head while preserving the duodenum — known as the Beger or FRY procedures.