Liver Tumors

1. Benign Liver Tumors

1.a. Cavernous Hemangioma

Hemangioma is the most common benign liver tumor. Its incidence ranges between 3% and 10%. It affects women more often than men, with a ratio of 6:1. It can occur at any age. They are supplied by the hepatic artery or its branches.

They are usually small in diameter and asymptomatic; they are generally discovered incidentally. Those larger than 4 cm may cause abdominal pain or be palpable as a mass. Rarely, they can lead to cardiac problems (cardiac hypertrophy and congestive heart failure) and coagulation disorders.

A definitive diagnosis can be made through imaging (scintigraphy, contrast-enhanced CT, MRI, or angiography). Therefore, biopsy is rarely necessary.

Most have a benign course, and complications (spontaneous rupture or bleeding) are rare. Therefore, most hepatic hemangiomas do not require treatment and are followed up with imaging. Symptomatic hemangiomas (rapid growth, pain) should be removed by lobectomy or enucleation. In cases not suitable for surgery, alternative treatment options include radiotherapy or embolization via hepatic artery catheterization.

1.b. Hepatic Adenoma

It accounts for about 2% of all liver tumors. It originates from hepatocytes. Hepatic adenomas occur in 90% of cases in women, most commonly between the ages of 30 and 50. Risk factors include the use of oral contraceptives (containing estrogen), hormone therapy, pregnancy, misuse of anabolic steroids, and glycogen storage disease. Recent studies show that diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and lipid metabolism disorders may also increase susceptibility.

Most patients are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally on imaging. Symptomatic patients may have right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, and abnormalities in laboratory tests (especially alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase). They may also present with acute intra-abdominal bleeding and shock.

They are usually located in the right hepatic lobe. They appear as solitary lesions of varying size (1–30 cm). Because imaging alone may not provide a definitive diagnosis and there is a potential for malignancy, biopsy may be required. Aspiration biopsy is safe, but core needle biopsy carries a bleeding risk. Excisional biopsy, performed laparoscopically or openly, may be preferred because of the risk of rupture.

Due to the small number of patients, there is no established treatment guideline. Management depends on the presence of complications (suspected malignancy, spontaneous bleeding, rupture). Malignant transformation (HCC) is more common in men and occurs in about 4.2% of cases, while bleeding occurs in 20–40% of cases.

Surgery is recommended for lesions >5 cm, those showing rapid growth, causing symptoms, associated with HCC molecular markers or increased tumor markers (AFP), male patients, and those with glycogen storage disease.

Some can be removed by wedge resection, but deeply located or large lesions generally require partial hepatectomy. Hepatic adenomas may regress after discontinuation of oral contraceptives or steroids, or after pregnancy. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy have no therapeutic value.

1.c. Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

It is the second most common benign tumor of the liver. Focal nodular hyperplasia is a benign tumor with no malignant potential. It occurs more frequently in women. Although most common in women of reproductive age, it can be seen at any age. It develops due to a congenital vascular anomaly (A_V malformation). Macroscopically, the tumor is well-circumscribed, firm, and usually presents as a subcapsular mass measuring 2–3 cm in diameter.

Most patients with focal nodular hyperplasia are asymptomatic. In symptomatic patients, lesions are larger (4–7 cm) and rarely multiple. It usually presents with right upper quadrant pain, discomfort, and sometimes a palpable mass. Diagnosis is generally made by imaging (ultrasonography, MRI). The presence of a central scar in contrast-enhanced imaging is characteristic. If absent, it can be difficult to distinguish from hepatic adenoma or hepatocellular carcinoma. Unlike hepatic adenomas, these tumors rarely enlarge or bleed.

If the lesion grows, causes pain, or if there is diagnostic uncertainty, surgery may be recommended.

1.d. Nodular Regenerative Hyperplasia

This is a diffuse hepatocellular pathology occurring in non-cirrhotic livers, characterized by multiple nodules and intervening areas of hepatic atrophy. It is often associated with portal hypertension. Treatment is generally directed toward managing portal hypertension.

1.e. Simple Liver Cysts

Liver cysts are common. They are fluid-filled structures and are usually seen in women. They can be developmental, secondary to inflammation, or post-traumatic. Liver cysts may also occur in polycystic kidney disease and parasitic (hydatid) liver diseases.

1.f. Pseudotumors

Pseudotumors differ from liver tumors in that they represent abnormal tissue proliferation rather than true neoplastic growth. Unlike cell proliferation, there is a “regional alteration” of the tissue. The problem is that they can be mistaken for liver masses in imaging studies. Examples of pseudotumors include hepatic fibrosis, fatty liver changes, and inflammatory pseudotumors.

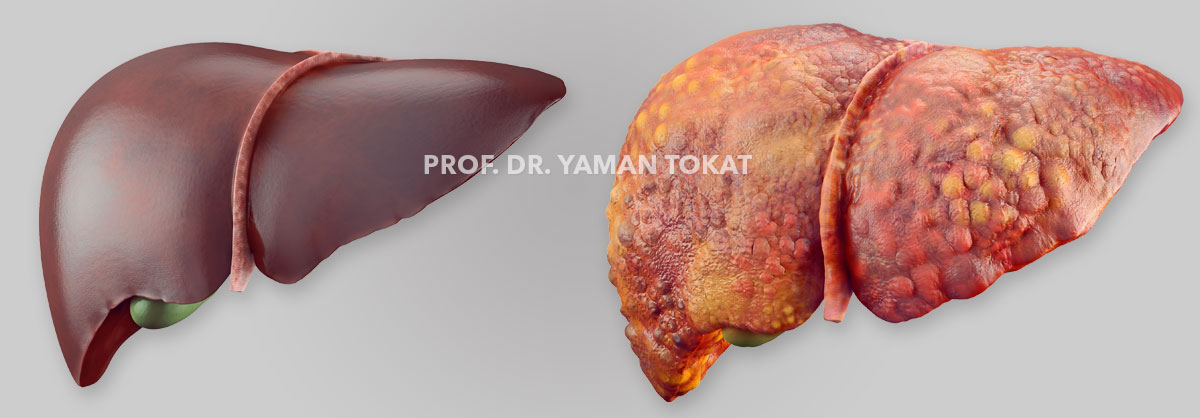

2. Primary Malignant Tumors of the Liver

Primary liver cancers are the 5th most common cancers worldwide and rank 2nd among the leading causes of cancer-related death. Approximately 95% of primary liver cancers consist of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (about 80–85%) and cholangiocellular carcinoma (CCC).

With the experience gained in hepatectomy procedures, advancements in systemic therapies, and the widespread use of local treatments, most patients can now benefit from combined treatments that significantly improve survival.

2.a. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

It frequently (80–90%) develops in patients with chronic liver disease. The average age of occurrence in Western countries is between 50 and 60 years, while it tends to appear at younger ages in Asia and Africa. It is 4–9 times more common in men than in women.

Chronic Hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV) infections are the leading causes worldwide. Other risk factors include alcohol use, aflatoxin exposure, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NASH) or steatohepatitis. The prevalence of these risk factors varies by region—for example, Hepatitis B is the most common cause in China, while Hepatitis C and alcohol are more common in the United States. Genetic causes include hemochromatosis and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

With Hepatitis B vaccination, a decrease in HBV infection and HCC incidence is expected. In contrast, in the United States, deaths related to HCV-associated HCC are among the fastest-rising causes of cancer-related mortality and are expected to increase further. It typically takes about 20 years after HCV infection for HCC to develop.

The most common symptoms appear as the disease progresses, including fatigue, weakness, loss of appetite, upper abdominal pain, and weight loss. Jaundice is evident in about one-third of patients. Several paraneoplastic syndromes may occur with HCC, the most common being hypoglycemia. Abnormalities may also be observed in serum proteins such as AFP, globulins, haptoglobin, ceruloplasmin, alpha-1 antitrypsin, ALP, and isoferritin.

HCC can be diagnosed through imaging. Typical findings on dynamic, three-phase CT or MRI liver protocols in patients with underlying liver disease and lesions >2 cm include early arterial enhancement, delayed washout, capsule enhancement, and progressive size increase. Small satellite nodules are common. In smaller lesions, findings may be less specific, but elevated AFP levels with similar imaging patterns should raise suspicion. If imaging findings are inconclusive or the lesion develops in a patient without known liver disease, a biopsy may be performed.

When determining treatment, tumor-related factors, liver function, and patient performance are key considerations. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system is the most widely used. For liver-confined disease, local therapies (thermal ablation—RFA or microwave, TACE, TARE—vascular therapy via hepatic artery, or radiotherapy) are preferred over systemic therapy as first-line options. Surgical resection has become more common, particularly for patients without metastasis, with normal liver function, or compensated cirrhosis without portal hypertension.

Based on randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses, long-term outcomes suggest that liver resection provides better results than RFA for lesions smaller than 5 cm, while outcomes are similar for lesions <2 cm. Surgical resection should still be considered for suitable patients with small lesions after evaluating other factors. Patients with tumors >2 cm should be evaluated for liver transplantation. According to the Milan criteria (a single tumor ≤5 cm or ≤3 tumors each ≤3 cm), liver transplantation is considered the gold standard.

The decision between resection and transplantation depends on organ availability, the patient’s overall condition, surgical expertise, and center resources. Today, outcomes for resections in tumors >5 cm and >10 cm have been reported to be similar to those for smaller lesions. Advances in liver resection techniques over the past 25 years have reduced operative and in-hospital mortality from 10–25% to below 5%. When negative surgical margins can be achieved, resection is always preferred over non-curative treatments.

If resection is not feasible, liver transplantation may be an option. Many of these patients require bridging therapies. For ineligible patients, systemic treatment modalities (molecular therapy, immunotherapy—immune checkpoint inhibitors, cytotoxic chemotherapy) may be used alone or in combination.

In patients with large tumors (unsuitable for TACE), immunotherapy-based systemic treatment is preferred over locoregional therapy. Combination therapy with atezolizumab and bevacizumab—or durvalumab and tremelimumab if contraindicated—has shown superior outcomes compared to molecular therapy alone. TACE combined with lenvatinib is another alternative approach.

The role of surgical resection in patients with vascular invasion remains controversial. These patients often have portal vein tumor thrombosis and are considered to have metastatic disease. While palliative therapy was previously recommended, systemic therapy followed by surgery in selected patients with distal involvement has recently emerged as an alternative.

If disease progression occurs during treatment or if extrahepatic spread develops, systemic therapy or lesion-directed interventions may be considered in patients with preserved liver function.

*Common sites of extrahepatic spread include: lungs (30–50%), diaphragm (10–15%), bones (5–20%), adrenal glands and peritoneum (5–10%). At diagnosis, about 60% of HCC patients already have extrahepatic metastases.

*In untreated patients, average survival after the onset of symptoms is approximately 4 months. The five-year overall survival rate is below 15%, and the cancer-specific survival rate is below 20%.

2.b. Cholangiocarcinoma

Another primary malignant tumor of the liver originates from epithelial cells of the peripheral bile ducts. It may present as intrahepatic (20–25%) or extrahepatic. The disease is generally sporadic. Risk factors include primary sclerosing cholangitis, choledochal cysts, various parasitic or toxin exposures, Hepatitis B and C, and the increasingly common problem of NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis). Only about one-third of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) patients are suitable for curative treatment.

Patients may present with abdominal pain, weight loss, or a palpable abdominal mass. Extrahepatic cases typically present with jaundice, while jaundice is rare in ICC. Laboratory findings show elevated CA 19-9 in about half of patients and elevated CEA in about 20%. Imaging findings in ICC may include bile duct dilatation and parenchymal atrophy. Tissue biopsy is the only definitive diagnostic method but is not mandatory preoperatively if imaging findings are supportive (hypoechoic mass on CT, delayed or venous-phase enhancement, bile duct dilatation and parenchymal atrophy, hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 MRI, and progressive peripheral enhancement). Biopsy is required for systemic therapy in inoperable cases.

Surgical resection is the only curative option, but few patients are eligible at diagnosis. About three-quarters of suitable patients require hemihepatectomy or extended hepatectomy, and negative margins are achieved in 80%. Nevertheless, long-term survival remains low, with a five-year survival rate of 20–30% after surgery.

Poor prognostic factors include multiple tumors, vascular invasion, regional lymph node metastasis, periductal invasion, and distant metastasis. R0 resection improves survival and reduces recurrence. Lymph node dissection is particularly important in ICC. The presence of nodal metastasis is one of the most significant prognostic indicators—when positive, the number of tumors and vascular invasion lose prognostic value. Therefore, portal lymphadenectomy is recommended in ICC. The right lobe drains to the hepatoduodenal ligament and the left lobe to the left gastric (lesser curvature) nodal area, both of which should be cleared during surgery.

Despite improvements in survival, about half of patients experience intrahepatic recurrence within the first year. During the first two years, most metastases (80%) occur within the liver, while after two years, most recurrences (60%) are extrahepatic. Overall, 80% of recurrences occur within two years.

Due to high recurrence and low survival rates, adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) and radiotherapy (RT) may be beneficial, especially in cases with positive surgical margins and/or lymph node involvement. First-line CT is typically gemcitabine plus cisplatin, and second-line options include FOLFOX or capecitabine. RT is preferred over ablation (RF or microwave), though radioembolization (TARE) can achieve better results when performed by experienced interventional radiologists. TACE also remains a viable option. Neoadjuvant therapy may be recommended for patients unsuitable for resection or with suspected nodal metastasis, as it helps assess tumor biology and increases the likelihood of achieving R0 margins during surgery.

Recent studies have explored the role of immunotherapy; although its safety and efficacy in this patient group have not yet been fully confirmed, clinical trials are ongoing. In ICC, the tumor microenvironment promotes tumor formation by suppressing antitumor immune responses. The goal of immunotherapy is to create a new tumor microenvironment. Therefore, immune checkpoint inhibitors, tumor vaccines, and genetically modified chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells may be used. Identifying predictive biomarkers to determine which patients will benefit is critical, and current research is focused on this area.

In some centers, this patient group is also included on liver transplant waiting lists. For highly selected cases of locally advanced, unresectable extrahepatic CC, transplantation can be an alternative option. Reported series show five-year survival rates between 53% and 82% for patients who received preoperative chemotherapy.

In conclusion, primary liver tumors cause significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Treatment is complex and depends on multiple factors, from tumor biology to the patient’s overall condition. For HCC, various treatment modalities (ablation, resection, transplantation) exist, with resection providing the best long-term outcomes in suitable patients. For ICC, surgery remains the only potential curative approach. Although similar oncologic surgical principles apply, portal lymphadenectomy is additionally recommended in ICC for staging and prognostic purposes. Despite successful surgery, both locoregional and systemic recurrence rates remain high. Therefore, adjuvant therapy after surgery or neoadjuvant therapy to render tumors operable should be considered. Given the diversity of patient, tumor, and treatment factors, a personalized, multidisciplinary treatment approach is essential.

3. Secondary (Metastatic) Malignant Tumors of the Liver

Metastatic or secondary tumors of the liver are approximately 20 times more common than primary liver cancers. Because of the liver’s filtering function, cancer cells that enter the bloodstream can become trapped in the liver and continue to grow. There are two types of metastasis: caval type and portal type. In the caval type (e.g., bone, breast, prostate, and kidney cancers), the metastatic route is through the hepatic artery. These may spread directly from the primary tumor or after passing through the pulmonary filter (as in lung or breast cancer). In the portal type, metastasis occurs from gastrointestinal cancers. Because blood from the digestive system first passes through the liver, the rate is high. Isolated involvement is common in cancers of the colon, rectum, small intestine, bile ducts, stomach, and pancreas. In colorectal metastases, elevated CEA and alkaline phosphatase levels are particularly valuable follow-up parameters.

The treatment of liver metastases depends on the origin of the primary tumor, the location and extent of liver lesions, and whether there is spread to other organs outside the liver.

In very well-selected cases, it is possible to successfully remove liver metastases from breast, stomach, some pancreatic tumors, hormone-secreting tumors (such as neuroendocrine tumors), testicular and ovarian tumors, and certain renal tumors, thereby prolonging expected survival. However, colorectal cancer metastases should be evaluated separately. The liver is the most common site of metastasis for colorectal cancer; one out of every four patients develops liver metastasis during the course of the disease. In this patient group, surgical treatment of liver metastases is of great importance.

As a principle, liver-preserving surgical approaches (such as hemihepatectomy, anatomic segmentectomy, atypical resection, or wedge resection) should be preferred over extended resections. Recurrence may occur in the liver or other organs even after surgical removal. To minimize this risk, surgery should be combined with appropriate chemotherapy and/or local treatments (e.g., radiofrequency ablation, ...).

Metastases that cannot initially be resected surgically may be downsized with appropriate chemotherapy combinations to make surgery possible. In cases where surgery remains unfeasible, chemotherapy is the main treatment. This can be administered systemically or locally, targeting only the liver. In such cases, the decision should be made collaboratively by the surgeon, oncologist, interventional radiologist, and the patient.

While life expectancy is quite limited in patients whose liver metastases cannot be surgically removed, long-term survival (5-year survival rate of 20–30%) is achievable in patients whose metastases are resectable. Outcomes for hepatic metastases from bronchial, gastric, and pancreatic cancers are less favorable compared to colorectal metastases.

Liver transplantation is another area of research for patients who are not suitable for surgical resection. Recently, staged surgical procedures such as ALPPS and RAPID have become preferred methods in this patient group. Moreover, in highly selected cases, 6–7 centers worldwide are currently involved in active clinical research projects performing liver transplantation for these patients. Published series show wide variability in outcomes (5-year survival rates ranging from 18% to 83%) and no standardized criteria. Proper patient selection is essential for success. Among molecular prognostic factors, the most commonly included are BRAF wild type and RAS mutations. Since most procedures are performed as elective living-donor transplants, perioperative risks are relatively low.

Note: The information provided has been compiled from recent data (last 5 years) from medical literature sources such as UpToDate, PubMed, and Google Scholar.