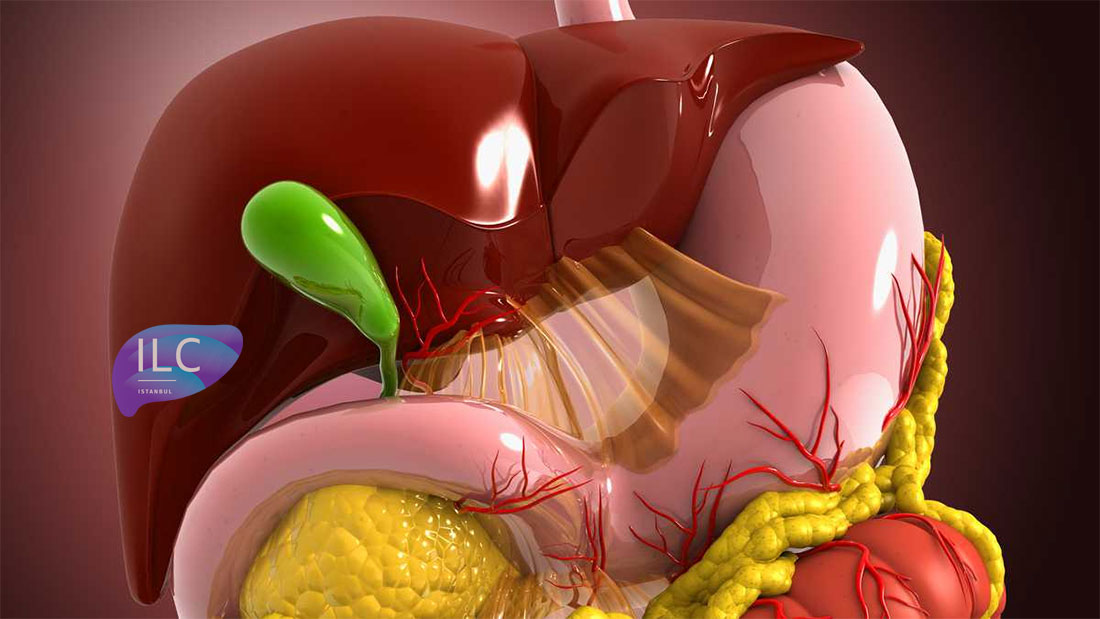

Gallbladder and Biliary Tract Surgery

Gallbladder Problems

Gallbladder problems are most often related to gallstones. Gallstones generally form from a combination of cholesterol and bile salts. The exact reason why some people develop gallstones is not fully understood, and there is no known method to prevent their formation. These stones may block the bile duct, causing pain and acute inflammation of the gallbladder (acute cholecystitis). If they migrate into the main bile duct, they can lead to jaundice or a serious condition called acute pancreatitis. Gallbladder cancer is associated with gallstones in about 80% of cases, though there is no scientific evidence that gallstones directly cause cancer.

How Are Gallstones Diagnosed and Treated?

The main symptoms of gallstones are pain in the right upper quadrant and/or the middle of the abdomen. This pain may radiate to the right shoulder, back, or flank. The most common diagnostic method is ultrasonography. Gallstones that cause pain or any complications require treatment. The only permanent treatment is surgical removal of the gallbladder. This procedure, which can be performed either as open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy, is among the most frequently performed surgeries. The laparoscopic method should be the first choice for all suitable patients, as it causes less pain, allows a shorter hospital stay, and ensures faster recovery.

Asymptomatic Cholelithiasis

Gallbladder stones are a common problem worldwide, found in 10–15% of the adult population in Western countries. Studies conducted in our country show a prevalence of about 6–7%. The vast majority of these stones do not cause any symptoms. Despite the low rate of symptomatic cases, the high prevalence of gallstones has made gallbladder surgery one of the most frequently performed operations. The failure of alternative treatments and the widespread adoption of laparoscopic cholecystectomy have led to an increase in the number of surgeries. Known advantages such as shorter hospitalization, better cosmetic results, and faster return to work have shifted both patient and physician perspectives, lowering the threshold for surgical indications.

Whether the advantages of laparoscopic surgery should lead to changes in surgical indications remains a matter of debate.

The widespread use of ultrasonography has resulted in the detection of many asymptomatic patients. Numerous studies have examined the natural course of asymptomatic stones. Most have shown that the majority of stones remain symptom-free for long periods, with symptoms or complications developing at a rate of 1–4% per year. In the first five years, 10% of patients develop symptoms or complications, and by twenty years, this rate increases to about 20%.

While there is no debate among surgeons about the necessity of surgery for symptomatic gallstones, there are differing opinions on the management of silent (asymptomatic) gallstones, both in the era of open surgery and laparoscopic surgery. Researchers have investigated whether any factors related to the stones can predict symptom development, but characteristics such as number, size, and composition have not been found to accurately predict the occurrence of symptoms or complications such as acute cholecystitis or pancreatitis.

The time between the formation of a gallstone and the onset of symptoms also remains controversial. Studies using carbon dating methods found that the average time between stone formation and symptom onset is about eight years. However, Gracie and Ransahof reported that symptomatic cases tend to appear within a shorter period. Similarly, in Lund’s study, most patients became symptomatic within the first five years.

There is also debate about whether the first symptom of gallstones is a serious complication or if pain attacks usually occur before complications develop. Many studies have shown that most patients experience symptoms before complications occur. However, in the series reported by Pickleman and Gonzales, 77% of patients presented with acute cholecystitis as their first episode.

In a study involving patients who were found to have gallstones incidentally during an ultrasound performed for other medical reasons, only 15 out of 139 patients developed biliary colic over a five-year follow-up period. Similar to other epidemiological studies, these results show that most patients remain asymptomatic.

Diabetes and Silent Stones

It is a widely held belief among surgeons that gallstones are more common in diabetic patients, that complications occur more frequently, and that these lead to higher morbidity and mortality. Ransahof reported that 14.8% of patients treated for acute cholecystitis were diabetic. Landau and colleagues found that diabetic patients had more bacterial growth in their bile, as well as higher rates of gangrenous changes and perforations in their gallbladders. Another proposed hypothesis is that autonomic neuropathy in diabetic patients masks the symptoms, leading to delayed diagnosis.

These findings led to the long-standing practice of recommending prophylactic cholecystectomy for diabetic patients. However, many later studies produced conflicting results. Perrson and colleagues, for example, did not find diabetes to be an independent risk factor for gallstone formation, and no significant difference in gallstone prevalence was found when diabetic patients were compared with control groups. While earlier studies reported higher mortality in diabetics with acute cholecystitis compared to non-diabetics, more recent research has shown that mortality rates are not dramatically different, although morbidity remains higher.

No significant difference was found between diabetic and non-diabetic patients in the natural course of asymptomatic gallstones. In the majority of diabetic patients, gallstones remain asymptomatic for long periods.

Comorbidities in diabetic patients increase the risk of complications leading to higher morbidity and mortality. Therefore, the management of asymptomatic gallstones in diabetic patients remains controversial. Studies have shown that routine screening for gallstones in diabetic patients is unnecessary and that cholecystectomy should not be routinely recommended for every patient. However, each case should be evaluated individually, and cholecystectomy should be considered in selected high-risk patients.

Asymptomatic Stones in Transplant Patients

Studies have shown that the incidence of gallstones is higher in solid organ transplant patients and that infectious morbidity is greater due to immunosuppression. These studies also reported that the rate of emergency post-transplant cholecystectomy is particularly high in heart transplant recipients. As a result, many transplant centers routinely screen patients, and some even perform prophylactic cholecystectomy.

However, because these studies were conducted on small patient groups, clinical practices vary across centers. In a series of 662 renal transplant patients by Melvin and colleagues, 52 (7%) required cholecystectomy, and complications occurred in six (11%) patients. No cases of graft loss were reported.

The general consensus today is that prophylactic cholecystectomy is not necessary in kidney transplant patients. However, due to the higher mortality following heart transplantation, prophylactic cholecystectomy may be justified in these cases.

Gallbladder Cancer and Stones

Sickle Cell Anemia and Silent Gallstones

In patients with sickle cell anemia, hemolysis leads to a higher incidence of pigment gallstones. Because abdominal symptoms during sickle cell crises can be confused with biliary colic or acute cholecystitis, many groups have recommended prophylactic cholecystectomy for this patient population. However, this approach was not widely accepted due to the morbidity and mortality associated with vasoactive crises following surgery in the past.

The introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, advances in anesthesia techniques, better understanding of factors that trigger vasoactive crises, and preoperative partial exchange transfusions to reduce HbS levels below 50% have made prophylactic cholecystectomy a safe option for these patients.

Incidental Cholecystectomy

One of the controversial situations in gallbladder surgery is whether to perform cholecystectomy when gallstones are detected preoperatively or intraoperatively during surgery for another condition. In a series of 109 patients undergoing colorectal, gastric, or gynecological surgery, 78 (72%) underwent cholecystectomy, while the gallbladder was left intact in 31 (28%) patients. Complications occurred in only two patients in the cholecystectomy group, whereas 13 patients in the non-cholecystectomy group developed symptoms, and seven required open cholecystectomy 2–11 weeks after laparotomy. Similar results have been reported in other studies. These studies also demonstrated that performing cholecystectomy in the same session is safe and does not increase the risk of complications.